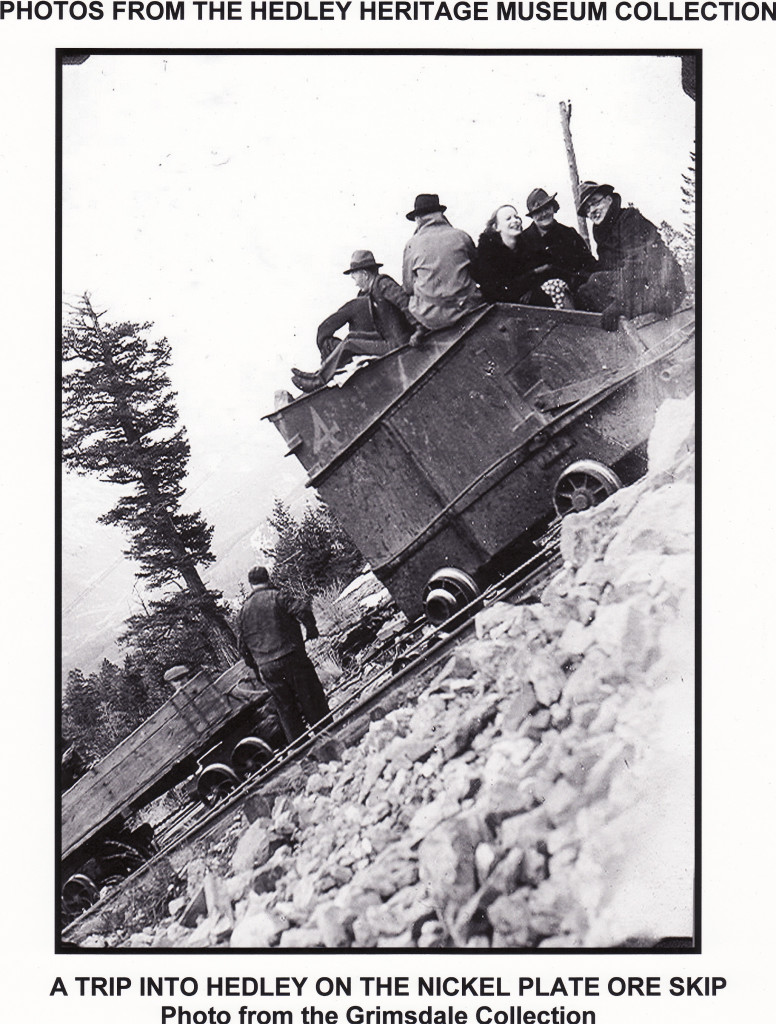

I have come to have a great deal of respect for the hardiness and ingenuity of the men who worked in the Mascot and Nickel Plate mines in the first half of the last century. The mines were high above Hedley and for those who had a wife and children in town, transportation was a constant challenge. According to historian Doug Cox, miners were allowed to ride in the skips used to transport ore down to the Stamp Mill. Permits were required, though, and they were limited. Tough and determined, the miners resorted to innovation.

I have come to have a great deal of respect for the hardiness and ingenuity of the men who worked in the Mascot and Nickel Plate mines in the first half of the last century. The mines were high above Hedley and for those who had a wife and children in town, transportation was a constant challenge. According to historian Doug Cox, miners were allowed to ride in the skips used to transport ore down to the Stamp Mill. Permits were required, though, and they were limited. Tough and determined, the miners resorted to innovation.

Cox says “some men got around the pass system by hiding near the upper ore bin until the skip had started down. Then they jumped on. The hitch hikers jumped off the skip before it reached the bottom ore bin and kept out of sight of the supervising staff. They skirted around the bluff, then down to the Hedley town site.”

In my opinion, it is the “broom riders” who were the most inventive and enterprising. In a letter to The Western in the June 20, 1990 edition, miner Bob MacRae (now deceased) wrote about placing a broom on one of the ore car rails and riding on it down the mountain. “This ‘broom affair’” he says, “consisted of a piece of rubber belting and a piece of tin channelled to fit the rail. It was nailed to an old house broom.” He wore old rubber boots for brakes and found that if he cut the handle off the broom, he could double his speed.

His record for a trip down the mountain was four and one half  minutes, including walking several flat stretches. On one occasion a worker had wiped grease on the rail and Bob’s rubber boot brakes became useless. His speed increased considerably. “I think I probably broke my record,” he says in his letter.

minutes, including walking several flat stretches. On one occasion a worker had wiped grease on the rail and Bob’s rubber boot brakes became useless. His speed increased considerably. “I think I probably broke my record,” he says in his letter.

Bob’s sister Effie, a Hedley high school graduate, told me he had a good reason to rush down the mountain after work each day. “Bob had a new English bride from Manchester.” When I asked her if her brother had been a dare devil type, she said, “oh no, he was very cautious.” Possibly there were things about Bob that Effie didn’t know.

In time, others joined Bob in broom riding. Not all copied his more advanced innovation. Some just borrowed a broom and rode down.

Ken Jones, a former miner now living on Old Hedley Road, tried it once, “just for the fun. I couldn’t get the balance or the speed,” he told me. “It wasn’t for me.”

In time, company officials banned broom riding, but this left them short of more than 20 miners due to lack of transportation. To make up the deficiency they brought in a bus, and Bob MacRae was one of 2 drivers assigned to driving duties.

Bob’s description of this assignment suggests the bus ride may have been more dangerous than riding the broom. “Snow, ice, rocks, cows, horses and deer on the road with numerous blind corners made it treacherous driving,” he said. “There was times I wished I was riding carefree down the mountain on my broom.”

I wonder what present day union bosses and the WCB would have to say about this practise. Unfortunately, I have seen no photos of these ingenious, hardy men racing down the mountain on their brooms.