Except for the persistent, meticulous research of Andy English andJennifer Douglass, the intriguing World War I story of the

Hedley “Machine Gun Boys” might have remained lost forever. Fifty-two young men, many of them working in the Nickel Plate Mine, signed up and went to war. Twelve gave their lives to the battle to combat the German Kaiser’s armies. They fought in the Battle of the Somme, at Vimy Ridge, and also Ypres. Many of those who returned had been gassed and wounded. Most suffered from shock. English and Douglass point out that for Hedley, a town of 400, it meant the loss of wonderful human potential.

It was Andy who initiated the research 2 years ago. “The 100 year anniversary of the beginning of the war was coming up,” he said. “It concerned me that some of the names on the Cenotaph were no longer legible.”

He had grown up in a family familiar with war. His grandfather signed up in 1940 and became an Armourer in the RAF. “He put the bombs on the planes. Much of the Battle of Britain took place over Surrey, where my family lived.”

When the German bombers came, the family rushed inside and hid in their “air raid shelter”, a reinforced table. Their home suffered blown out windows and a cracked foundation. “While I was growing up, the family talked about war a lot.”

Jennifer’s background is radically different. Her father, best selling author James Douglass, is a well known antiwar activist. Her grandfather 4 generations ago was in the Confederate cavalry. “I’ve long been interested in Hedley history,” she said. When Andy asked her to help with an exhibit at the Hedley Museum, she agreed and has become a committed research partner.

According to Andy, the online opening of the Attestation and Service Records made their research more productive. They devoted many hours to perusing museum records, studying the defunct Hedley Gazette, contacting family members, and delving into any possible source.

Hedley involvement in the war began when William Liddicoat signed up in the summer of 1914.“After the war,” Andy said, “he again worked in the mine and then started a dairy farm in Keremeos on what is now Liddicoat Drive.”

At least 10 more men signed up before Travers Lucas, an army captain and recruiter came to town in August, 1915. Deeply moved by Lucas’ presentation, another 17 men signed up. One of the men, Alec Jack, a bank clerk walked out of the bank and enlisted. He would later win the Military Cross and become a company commander. Another recruit, Bert Schubert worked at Schubert’s Merchandise. Jack Lorenzetto, the only one born in Hedley, was of Aboriginal/Italian descent and had grown up on the local reserve. He was conscripted in 1918. In a letter home he mentioned he was the second best shooter in his unit.

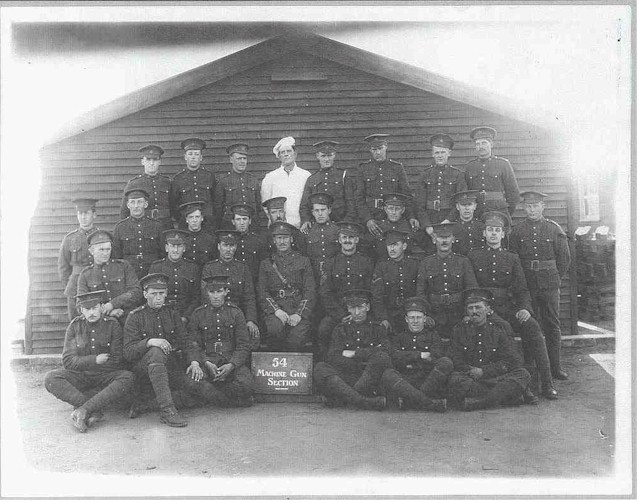

When the men recruited by Lucas departed for Penticton in 5 banner bedecked cars, the whole town turned out to bid them farewell. “The Stamp Mill whistle blared,” Jennifer said. “They rang the fire bell and also the school bell. The town band played rousing music to send them off.” Later the Hedley Cenotaph was sited on the very spot where they gathered for the departure. Many of the Hedley Boys became part of the 54th Battalion. Probably due to their mining experience, some were assigned to the Canadian Engineers.

The Hedley Boys wrote numerous letters, some to family and friends and others to the Hedley Gazette. “Their letters were wonderfully descriptive,” Andy said. “There was a deep sense of identification with Hedley and the Similkameen Valley. Even those who had come from England referred to each other as Hedleyites. They mentioned Hedley in every letter.”

“A number of the letters expressed appreciation for the socks knitted by the ladies,” Jennifer said. “They were also thankful to the people of Hedley and the Nickel Plate mine for Christmas packages.”

The Hedley contingent developed close relationships. When Ebenezer Vans died of illness in England, his unit put together the funds to buy a headstone for his grave site.

They were called the Hedley Machine Gun Boys because a number

were assigned to a machine gun unit. Most were accustomed to hard work in the mines. They were strong and fit, able to carry the heavy guns. It was a dangerous assignment, due to the enemy’s determined efforts to silence these effective weapons. Because it was so hazardous, toward the end the machine gunners were called “the Suicide Club.”

Private Sid Edwards, a machine gunner, was the first Hedley boy

killed. After his death the people of Hedley raised money to buyLewis machine guns. The initial campaign raised $3,500, sufficient to buy 3 guns. In all, 11 Hedley Boys were killed in action, a very high ratio compared to other units.

By the end of my conversation with Andy and Jennifer, I had a sense of their tremendous passion for the subjects of their research. “We feel like we have gotten to know them,” Jennifer said. “We’re continuing with the research,” Andy added. “We want the Hedley Machine Gun Boys to be remembered. ”

Because the lettering on the Hedley Cenotaph is becoming difficult to decipher, on Remembrance Day they will begin raising funds to remedy this. They want to refurbish the Cenotaph and possibly attach brass plaques with the names engraved. Anyone wanting to support this worthy endeavour can leave a message at the Hedley Heritage Museum (250-292-8787) or contact them directly.