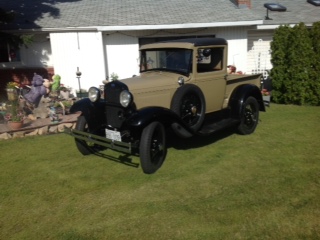

When I was told Gordon Glen of Keremeos owns a very pretty, restored Model A half ton pickup truck, I was intrigued. Possibly my fascination stems from early experience. I was about age 5 when my parents decided to move from rural Manitoba, not far from Steinbach, to Abbotsford, B.C. Dad bought a Model A, which he was confident could weather this arduous trip via Stevens Pass in the U.S. There were 6 of us in the car, my parents, sister Vi, plus 2 paying passengers. Amazingly, we encountered no mechanical difficulties. For a couple of years Dad drove the Model A every 2 weeks to his job at a logging camp near Hope. Having this experience in my history, I phoned Gordon and invited him and his wife for a visit.

When they arrived, he introduced us to Sam. Sensing our puzzlement she explained, “My name is Joan but my Dad tagged me with the name “Sam” when I was a kid. It has stuck and I’m happy with it.”

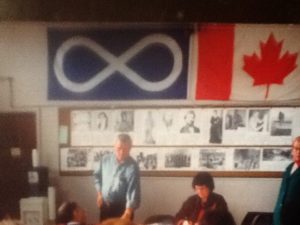

Sitting around the table in our sun room, Gordon said, “We’ve both been married before, we both have a set of twins, and we both lost our spouses through illness. About 5 years ago, a mutual friend introduced us at the Keremeos Legion. We were married a year ago.”

Sam, a slim blonde, has her own experience with vehicles. At one time she owned a T Bird and still has a rag top VW convertible. Equally interesting, she drove semi trailer transport trucks all over Canada and the U.S. for 15 years. Having a Class 1 driver’s licence, she was qualified to drive the fire truck at the Williams Lake volunteer fire department. “Often the men were away at their jobs during the day, so I drove,” she said.

Our conversation turned to the subject of Model A’s. Gordon’s experience with the iconic cars goes back to his early years. “Our neighbour had a Model A,” he recalled. “One summer my two older brothers worked for him. At the end of the harvest he gave them the old car for payment. We used it to haul potatoes and bring the cows in from the field.”

Eventually the brothers tired of the Model A, parked it in a slough, and departed the farm. “When I was 17,” Gordon said, “I asked for the car and they gave it to me.”

Having heard there are still a significant number of the much loved Model A’s tucked away in garages across this continent, and even around the globe, I asked Gordon what is so special about the car. “They’re almost completely constructed of steel,” he said, “Dodge and Chevrolet used wood and they didn’t last as well. While other companies lowered standards to keep prices down, Ford continually raised the bar and still kept the cost of the car affordable to any working man. They have a simple design and are easy to maintain. Some farmers actually turned their Model A’s into tractors for farm work. Even today all the parts, including tires, are available.”

Then he added, “I’ve been surprised by how well the Model A runs. It’s intended to go up to 45 mph, but is actually capable of higher speeds.”

The Model A was in production from 1927 to 1931. “The first couple of years they were quite small,” he said. “I’ve heard that Henry Ford wanted them small so that couples could not comfortably have sex in them.”

In time, Gordon sold his Model A with the understanding the owner would restore it. Some years later he again wanted to buy one, but owners were not selling. He bought a 1941 half ton Dodge. “It was my answer to not finding a Model A,” he said. “When we moved from Moose Jaw to B.C., driving it was like driving a Sherman tank.”

Acting on a tip from his brother Al in Vancouver, he finally located a Model A for sale, a 1930 pickup. “I bought it on the spot,” he said. He also joined the Lions Gate Model A Club and is still a member. “I’ve done a lot of upgrading on the truck. Members share knowledge and tools with other members.”

“I don’t golf, do sports, garden, or gamble,” Gordon said at the end. “For me the Model A is a good hobby.” Sam nodded and smiled. She’s just as hooked.