During my time at Community Services, I continued in my

volunteer role with M2/W2 at the Matsqui prison. I also remained on the M2/W2 Board.

At about the same time the government pulled the Community Services contract enabling me to work with seniors, Cal Chambers , chairman of the M2/W2 Board made an unexpected announcement. “Ray Coles, our Executive Director and Al, his assistant, have both given notice of their resignation. Both men had come from the Salvation Army and were friends. It was not entirely surprising they had decided to leave at the same time.

This development came as a shock to Board members. Who would replace them? The path ahead suddenly seemed uncertain, and the faces of the men around the table became sombre and troubled. We were not given a reason for their departure, but we knew the organization’s income was meagre. Possibly there had not been sufficient funds for their needs. The work needed to carry on, but who would take on their responsibilities? Most qualified individuals would expect more than the organization could pay.

Within the past year Ray Coles, with the approval of the Board, had applied for funding to create 4 new positions. I had been interested in working for M2/W2. The organization’s approach to re-claiming the lives of prisoners appealed to me. However, Ray Coles had not considered me for any of the proposed positions. He had promised them to individuals who were close to him. When the application for funding was turned down, the whole idea came to nothing.

I wondered now if the resignations might provide an opportunity to come on board as a staff member. I felt drawn to a role that would enable me to have more personal contact with inmates and prison workers. It seemed to me that my degree in sociology, the time at Community Services, being on the Board of M2/W2, and guiding our program at Matsqui Institution had prepared me at least somewhat for this. While the disheartened discussion went on around me, I arrived at a decision.

A pause in the dialogue provided me with an opportunity to speak of my interest. “I have thought for some time that if the opportunity ever came,” I said, “I’d be interested in having a full-time role with M2/W2.”

I didn’t attempt to sell them on the idea. They already had a sense of my character and they were aware of the work I was doing at Matsqui, running our program there. The decision should be based on their evaluation of me and whatever abilities they saw in me.

Vern Reimer, Executive Director for the Mennonite Central Committee in B.C. spoke first. “MCC could take you on under our Voluntary Service program,” he said. “We would pay all your living expenses and there would be something for extras. It wouldn‘t be great pay but you would always be able to count on it.” With Linda not working anymore, I knew this would make for a somewhat lean family economy. Still, I felt it was an idea we should consider. The example of our parents had taught us to be prudent in the realm of finances.

Les Pritchert, a pastor and very capable Board member said, “If Art agrees to take a full-time position, I’d be willing to assume the role of Executive Director on a part-time basis, until we find a permanent replacement.”

I knew Les only as a Board member. He had an incisive mind and a determined “let’s get things done” approach. He was experienced, focused, tenacious and driven. I was intimidated by the thought of working with him. The challenge intrigued and enticed me, though. After a discussion with Linda, I agreed to the arrangement.

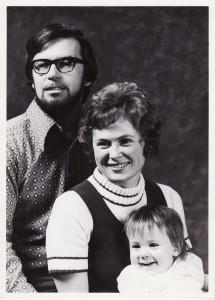

Within a short time, Linda, 9 month old Vivian and I were on a plane to Akron, Pennsylvania for the MCC orientation. Here we met volunteers going to various places around the globe, mostly to developing countries in desperate need of skills in trades, medicine and teaching. I recall particularly a bus trip to Washington, D.C. where we met MCC personnel who sought to positively influence government policy. By the end of the orientation, Linda and I felt great respect for what this fairly small but effective organization was accomplishing. We were pleased to be sponsored by MCC.

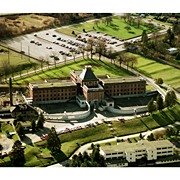

At that time the M2/W2 office was at 533 Clarkson Street in New Westminster. Most days I drove in from our little 5 acre farm in what was then Matsqui Municipality, near the Canada-U.S. border. In addition to Oakalla and Matsqui Insitituion, the organization had made contact with the BC Penitentiary and also Mountain Prison near Agassiz.

Fortunately, I learned that Les had a wonderfully congenial side. Although he was extremely immersed in other roles, he found the time to fully support and encourage me. Maybe he sensed that he would not live into deep old age and that he must not allow himself to be diverted from the objectives he considered most important. Although our time together was too brief, I was blessed to have him as a role model.

For me it was the beginning of an exciting, challenging chapter of my work life. My responsibilities would take me into virtually every prison on the Lower Mainland and in the Fraser Valley. I would interact with wardens, parole and probation officers, counsellors and security officers. I would deal with men doing time for murder, robbery, trafficking in heroin and cocaine, etc. And I would see citizen sponsors bring a ray of light into lives that had been darkened by crime, substance abuse, dysfunctional relationships and unfortunate choices. It would be an opportunity to work with sponsors to make a significant difference in the lives of men who had long ago lost their way.