When Linda and I stopped for coffee at Manning Park yesterday, we met several individuals who had just completed hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. One of them was Jay, a young man probably a little upward of age 25. He sported a black beard a lot of men would envy. His lean physique reminded me of mountain men I’ve seen in movies. I asked if he had been hiking in the park.

“I’ve actually just come off the Pacific Crest Trail,” he said. “I started in Campo, California 175 days ago.” He looked down at his feet and said, “this I my seventh pair of runners. I wore out 6 pairs.

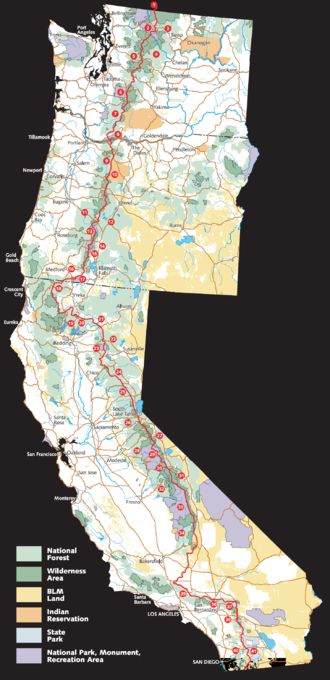

Most of those intrepid individuals who walk the entire trail begin at the southern terminus near the U.S. – Mexico border. In length it is 4,286 km. (2,663 miles) and reaches an elevation of 4,009 meters (13,153 ft.). The trail traverses California, Oregon and Washington, ending at Monument 78 at the U.S.- Canada border. This is on the edge of Manning Park.

Adriana answered the phone at Manning Park Lodge when I called with a few questions. She estimated they see 40-60 of these long distance hikers at the park each year. “They begin arriving sometime in August,” she said. “By the end of October the last ones have straggled in. They’re always pretty thin.”

While I was talking with Jay, Linda approached another young man who had also just completed the trail.

“You appear very fit and lean,” she said.

“Yes,” he agreed. “Doing the trail, you lose all your body fat.”

A young woman standing nearby was listening intently, then broke in. “I’ve just come off the trail today,” she said. “I didn’t lose all my body fat. It doesn’t seem quite fair.”

It is believed that about 300 hikers challenge the trail each year. About 180 complete it. It is also common to attempt only a portion of the trail. Probably the most common reason for failure to complete the entire length is running out of funds. Some hikers have re-supply packages sent to themselves at postal outlets or general stores in communities along the way.

Planning and commitment are considered essential. It is a gruelling trek and there have been occasional deaths. A variety of health related issues can also develop. Jay, a software engineer in San Francisco suffered a broken foot along the way. “Probably a stress fracture from all the walking,” he said.

Jay’s enthusiasm for the adventure and also his trim body made me a little envious. Although I’m somewhat past my “best before” time in life, the spirit is still willing. I rather doubt I could persuade Linda, but the Pacific Crest Trail does appeal.