As happens so often, we were sitting at the table in our sun room in Hedley. Derek Lilly was drinking his coffee black and reflecting on his Metis heritage. “The history books don’t tell the whole story about who played significant roles in Canada’s early development,” he said.

Derek was 10 when he came to Hedley with his mom and stepfather. “I looked up at the mountains and felt at home immediately. About a year later the folks decided to move on. I didn’t like their lifestyle so I stayed with my grandparents. They had moved here earlier and were pretty straight people.” His decision to stay was an early demonstration of an ability to make sound choices.

“Although my mom appeared aboriginal, I wasn’t really aware of my Metis heritage at that time. It wasn’t talked about in the family. On my birth certificate I was actually registered as French. They just tried to fit in,” he said.

In grade 10 he dropped out of school and joined the armed forces. After a 4 year stint he returned to Hedley and worked for the One Way Adventure Foundation as a youth counsellor. Here his friendship with a young couple resulted in a spiritual conversion. “This produced a change in how I looked at life,” he said. “I married Noree and not long after we moved to Winnipeg. There I earned a BA in General Studies at Providence University College and Seminary.” Courses such as logic, ethics and philosophy suggest he already had the capacity to mentally wrestle with difficult issues.

In 2004 Derek was hired by the Upper Similkameen Indian Band to run their tourism program. “They were just completing the stairs high up the mountain at the Mascot Mine. I was involved in developing tours. It was during this time that Phillippe, band business manager, encouraged me to check out my Metis heritage. I followed his advice and it changed my life.”

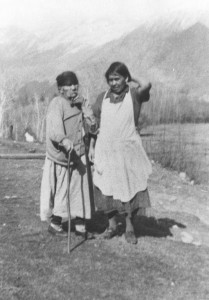

He learned that one of his early grandfathers, John McIver, had come from Scotland. The other, James Lilly, had emigrated from England. Both were probably less than 20 years old. “They worked for the Hudsons Bay Company as fur traders,” he said. “James Lilly’s Day Book is still in the HBC archives in Winnipeg.” Like many European men, they took aboriginal wives and had families. McIver’s first wife was Inuit. When she died, he married a Metis woman.” Unlike some, both McIver and Lilly stayed with their wives and children.

“In 1811 the HBC granted a large tract of land to Lord Selkirk. He created the Red River Colony, now Winnipeg, near the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers,” Derek said. “He wanted to provide land for retired fur traders. he lots were long, each with frontage on the Red River. My forebears were among the Metis who received lots.”

The Metis were prosperous farmers for a time, but their lives were not trouble free. Difficulties included an infestation of locusts, drought, the government’s desire to push them out, and the Riel Rebellion. Eventually they sold their lots and dispersed to various locations.

In time, some of the Lilly family made the migration to Hedley. For Derek this was fortuitous because it led him into his Metis past. He needed to rigorously study Aboriginal history and culture to run the Mascot Tours, and then represent the Aboriginal Tourism Association of B.C. in their Pavillion at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. He also organized tours of Stanley Park for the association’s Klahowya Village.

I asked Derek how his life has been impacted by his Metis heritage. “I never knew my dad,” he said. “What I’ve learned about our history has helped me understand where I came from, who I am, and where I’m going. I also have a better understanding of my mom’s life. Learning about the role of my ancestors in building Canada has given me a greater sense of belonging in this country, a sense of pride.”

Derek has contributed to the Hedley community. He was Fire Chief for 18 years and still serves as duty officer one day a week. Currently he is on the Hedley Grace Church Leadership Team. When he retires from his job as an industrial electrician at the pellet plant, he hopes to be more involved in Aboriginal work. The young man who quit school in grade 10 has done a lot to make Metis and Aboriginal people proud.