For many years a diminutive white chapel perched like a beacon of hope on a bluff overlooking Highway 3, just east of Hedley. When a month had a fifth Sunday, a priest arrived to conduct mass for a handful of parishioners, most of whom came from the two local reservations. In spite of the evils of church run residential schools, for me the chapel seemed a symbol of purity, exuding an aura of authenticity and a refreshing lack of ostentation. For some band members though, it likely stirred bitter memories of prejudice and abuse. On June 26, 2021, shortly after unmarked graves of children were discovered at a former Kamloops residential school, an arsonist put a match to this iconic structure.

Some time after the fire Linda and I attended a Wake for a band member and we were greeted warmly by Carrie Allison, a revered member of the local band. She told us there is still an earlier chapel, situated at a lower level on the same property. “Come and have a look,” she invited. “I’ll give you a tour.”

Several weeks later Carrie showed us the unpainted original chapel and also the small log structure that once served as the band jail. After the tour she sat with Linda and me in our Sun Room and talked about her life and the two chapels. “The first one was built in about 1890,” she said. “The white one was built in 1910. The people worked tirelessly, bringing building supplies with horse and wagon. It was very hard work. The elders who built them are gone now. I still do the cleaning and arrange for maintenance. I want to show respect for their efforts and sacrifices.”

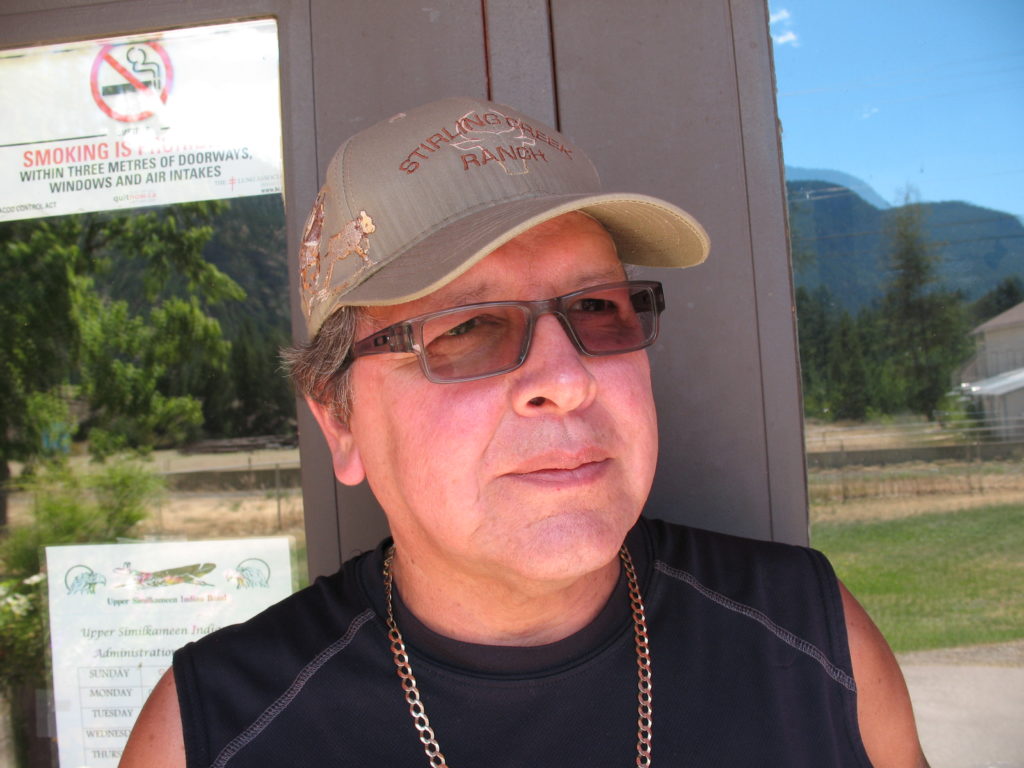

photo by Gerry Wilkin

Listening to Carrie, we wondered how she was able to rise above prejudice and difficult circumstances to become an inspirational role model to many in our community. Certainly her early years could have fostered a resentful, rebellious spirit.

“I was born in Merritt almost 92 years ago,” she said. “My birth father was white, a bad man. I didn’t get to know him.”

Like many indigenous children, Carrie didn’t get a great start in life. Her education began in a reservation school but at age 8 she was sent to a residential school in Kamloops. “Some of the nuns were nice,” she recalled, “but not all. One was especially mean to young children. We were in class half a day and worked half a day. We planted and weeded the crops. My mother had taught me to sew and I mended the boys’ pants, socks and shirts. If we didn’t make our beds perfectly, they were ripped apart and we had to start over. At meal times we saw the priests and nuns eating nutritious meals, including meat. Our meals were skimpy, with no meat. At Easter they gave us each a boiled egg with our meal. I was always hungry.”

She was 10 and had been in the residential school three years when her older sister refused to go back. “I decided not to go back either, so I ran away,” Carrie said. “I walked 8 miles to my grandparents home. My grandfather told me if I wasn’t going to school, I’d have to work. They couldn’t afford to feed me. I worked in orchards, did gardening and housework. Later I also worked in a restaurant.”

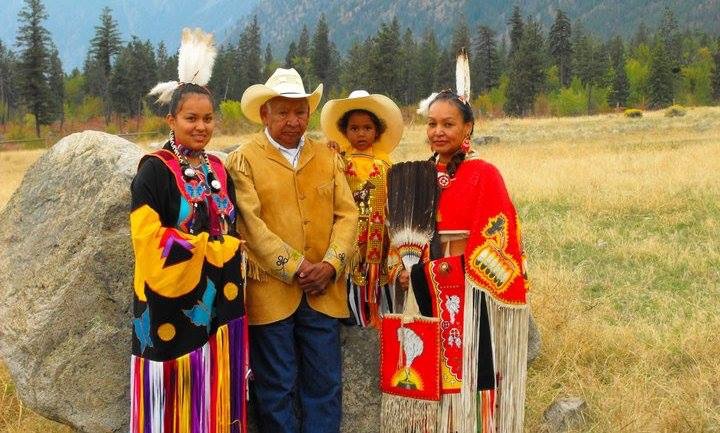

In 1949 at age 18 she married Edward (Slim) Allison, who later became band chief. At age 40 she returned to school and achieved a grade 10 standing. She decided to become a hair dresser and set up a salon in her home. When she was 60, Carrie applied for a social insurance card. “My mother couldn’t read or write,” she recalled. “She told me I was born on March 6, but when the card arrived, it said March 27.”

Carrie isn’t one of the bitter ones. Following her mother’s example, she still helps elderly and poor people in need. “When people ask how I can stay with the Catholic church after the abuse and humiliation of the residential school system, I tell them it wasn’t God who did that to me. People did it.”

Still vibrant, resolute and active in the local band, she will celebrate her 92nd birthday in March. Her good will, wisdom and resilience continue to be an example and inspiration to the band and the Hedley community.