(This blog was first posted June 12, 2019). After my father fell at age 89 and broke a hip, he never walked again. His previously robust body lost the capacity even to turn over in bed. Although he had long been a powerful force in my life, it was in his remaining 6 years that his values and approach to life most profoundly impacted me.

Dad was a cat operator and during most of my early years, he lived and worked in remote logging camps. I recall being awakened very early on a Monday morning to see him leave for work. I wouldn’t see him again for 2 weeks. In those years he was little more than a stranger to me.

When I was a teen, he brought the big red International TD 18 bulldozer back to the Fraser Valley where we lived and began clearing land for farmers. During my summer breaks from school, he took me along to his jobs. He wanted me to develop work skills and taught me to operate a bulldozer, drive a dump truck, use a chain saw and blow up huge old growth stumps with 20 percent dynamite. I began to understand that he possessed an uncanny ability with machinery.

Sometimes I shuddered inwardly watching him tackle a towering fir tree, or building a road down a precipitous hillside. I shuddered even more when he told me about constructing a logging road on the side of a mountain. “When I lifted the blade of my cat,” he said, “I could see the river a thousand feet below.” I knew that a slight misjudgment could have sent him and the machine hurtling down into the abyss. It seemed he harbored a need to taunt fate. Being young and impressionable, I respected his masculinity.

Although I wasn’t yet aware of it, my father was also influencing me at another, more important level. Only later did I understand he was a man of immense integrity. He didn’t lie, cheat customers, or complain when the going was tough. He reached out to people in need whether it was bringing a hitch hiker home for a meal or helping a non-mechanical neighbor replace a clutch in his car. He served on the executive of the parent group in my school and tithed faithfully to his church.

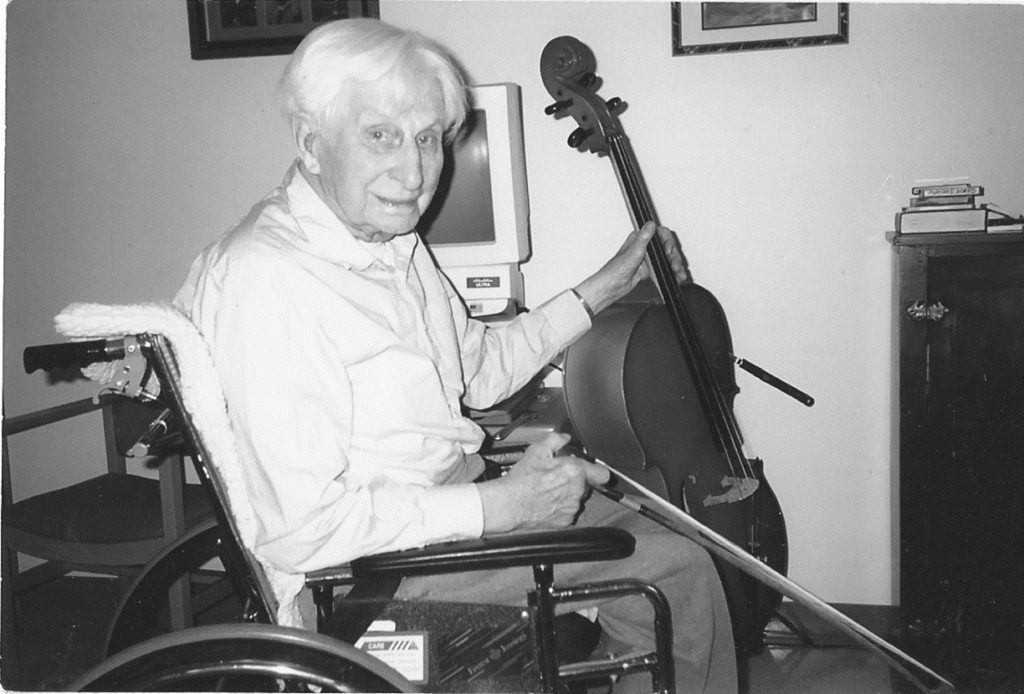

In my early 20’s our paths diverged when I attended S.F.U. Dad turned to music, playing first a bass fiddle and later a cello.

After he retired and mom passed away, my strong, self-reliant father wanted his family to draw nearer. He had for some years been battling prostate cancer and his PSA numbers were disturbing. He was living alone in an apartment when the life changing fall took away much of what had given him a sense of deep fulfillment.

Placed in a longterm care facility, he embarked on a disciplined exercise and stretching regimen, hoping to get his walking back. I asked one day if he needed to lie down and rest. Acutely aware the number of days he had left was shrinking, he replied ,“No, I don’t want to waste my time. I should be accomplishing something.” I marveled at how valiantly he pressed on, building a new life within the confines of the care facility.

A musician came weekly to help him again play the cello. I began plunking on the piano in the dining hall and together we made music for the residents. He asked the care aides about their families. They came to respect and love him. In time he became almost a local celebrity in the facility. Residents, visitors, care aides and nurses knew Jacob.

“I still like to live,” he said. But he was losing strength, the PSA numbers were creeping up and his hemoglobin was low. Near the end he was confined to his bed. I more often saw the pain lines on his face. Standing beside his bed holding his hand, I sometimes needed to turn away so he wouldn’t see my tears.

Dad didn’t complain. To the end he trusted God to see him through to “take him home” when he drew his final breath. I received the call from the facility at 5 am on December 9, 2009 telling me he had passed on. Even now I consider myself privileged to have been close to him during those last 6 years. It is still my desire to walk as much as possible in my father’s footsteps.