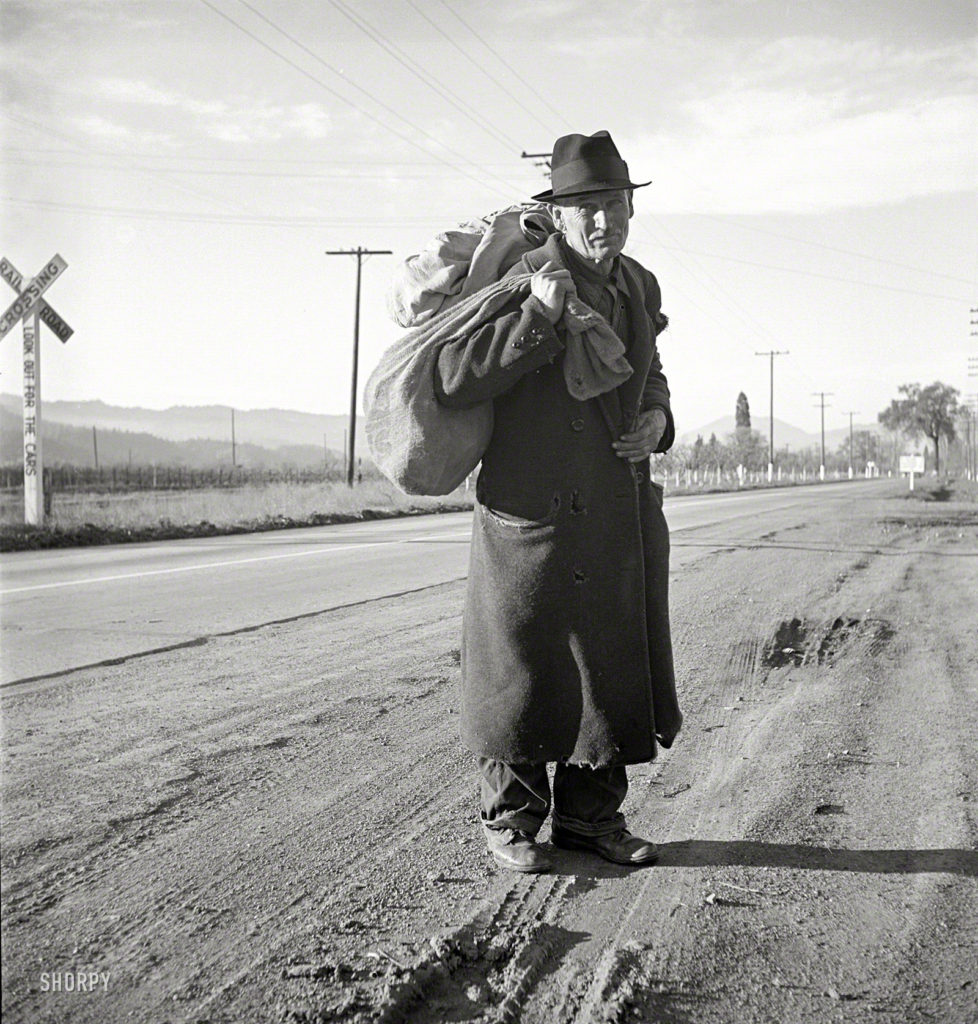

Travelling to the coast on the most serious smoke day a couple of weeks ago, I was surprised at the scarcity of vehicles going west. Equally surprising was the incessant flow in the east bound lane. Was everyone in Vancouver leaving due to the dense smoke? I was reminded of rats scurrying from a ship about to sink.

In Abbotsford the smoke hung like a thick, virtually impenetrable shroud over the city. Wanting to walk after several hours of constant sitting, I donned a mask and ventured out into this world of grey. We were staying with Linda’s Mom who lives in a 55 plus complex. Usually I encounter seniors walking their miniature versions of man’s best friend. Their pace is invariably interrupted by myriad inspections of hydrants and other sources of alluring aromas. On this day the streets were bereft of these elderly walkers. They weren’t willing to endanger their own health or that of their little companions. Overnight, the world had become unsafe.

It’s well known that the smoke came to us courtesy of our neighbours south of the 49th Parallel. Most environmental specialists believe the fires in California, Oregon and Washington are increasing in frequency and ferocity due to global warming, much of it caused by humans. I told my friend Howie about our experience with the smoke. I also somewhat unthinkingly mentioned that Linda and I restrict our driving because we don’t want to burden Mother Earth with more toxins.

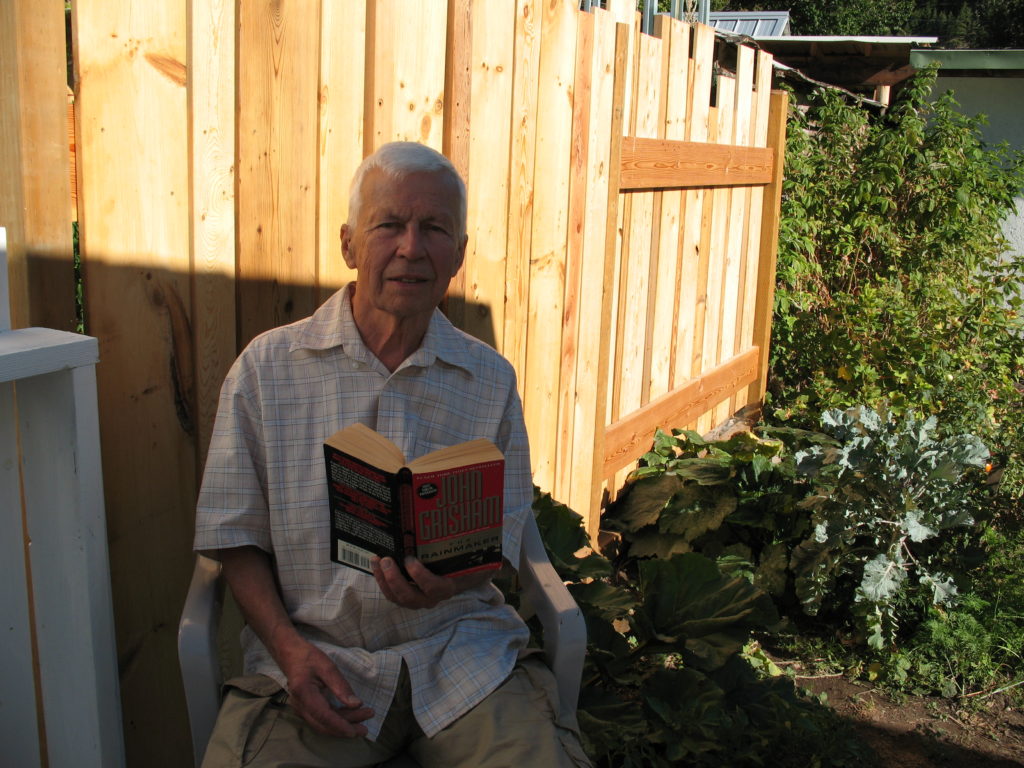

Howie is a committed curmudgeon, an ardent admirer of Donald Trump’s views, and invariably ready with a diatribe against any suggestion individuals can take action to protect the environment. Howie coughed several times, sputtered with indignation and said, “don’t you know there are millions of cars in the world? Think of the hordes of people in China and India who drive cars.” He snorted his derision and said, “anything you do won’t make a difference. Besides, there was global warming thousands of years ago. You need to read history.”

Some prominent world leaders harbour similar views. In Brazil huge swaths of wetlands are currently on fire. Thousands of animals, including jaguars, deer, monkeys, reptiles and serpents have been burned or displaced. In some areas many thousands of birds are falling from the sky. Even so, President Bolsonaro has weakened environmental protection. He claims reports of environmental degradation in Brazil are a lie.

The Australian fires have received extensive media attention, but fires in other places like Siberia and Argentina are receiving only scant coverage. In Canada we witnessed significant devastation from the Fort McMurray and Kelowna fires, but now that they are out, our focus has again shifted to personal pursuits. When a crisis is over, it’s easy to forget and become complacent.

Although I believe Howie views environmental history through a biased lens, he’s correct in urging me to look at past catastrophes. In “Collapse,” Jared Diamond cites numerous examples of societies whose activities devastated their environment and way of life. “Easter Island is a clear example of a society destroying itself by the over exploitation of resources,” he states. “They cut down all the trees on the island and no longer had wood for fires to keep warm, cook food, or construct canoes for fishing and trading. In time rats were the only source of wild food.”

Growing up in Abbotsford, my friends and I had no inkling such a future was possible. We roamed in the woods, drank from the streams, and never detected foul odours in the air, except near farms. Eight years ago Linda and I moved from there because the air had become unhealthy and unpleasant. In some mega cities the air has become dangerously polluted and citizens need to wear masks to survive.

According to the Climate Clock in Manhattan’s Union Square, humans have about 7 years to change course. After that the damage to the planet will be irreversible. We should expect that in time, the devastation may reach even into the Similkameen Valley. Thinking back now to the dense smoke and unpleasant air in Abbotsford, I wonder, “Is this our future?”

In spite of my curmudgeon friend’s scorn, I believe each of us can do something to protect our planet and ourselves. David Miller of the World Wild Life Federation put it succinctly when he advised us to “take care of nature, so nature can take care of us.”