Over a lifetime of celebrating numerous birthdays and drinking too many cups of strong coffee, I’ve become intrigued by the ways humans respond to various types of adversity, especially loss of freedom. Having set foot in more than a few West Coast prisons, and some long term care facilities, I’ve had plenty of opportunities to observe people who have lost the liberty to move as they please. In prison they are often constrained by chain link fences topped by razor sharp berka wire. Within high security prisons there are cells with sturdy locks on steel doors. Even seniors care facilities often have locks on perimeter doors. Seeing television coverage of crowds on the streets of large cities protesting covid related restrictions, I began thinking of the various ways in which I’ve seen people respond when their freedom is eroded.

One individual I liked to observe was incarcerated at Matsqui Institution. A 67 year old, chain-smoking veteran of the provincial and federal prison systems, Albert had invested at least half his years in prison. Addicted to heroin, he had long been a street level trafficker, at a time when our courts were still sending even small scale drug dealers to prison. Albert had never had a vision for more. When I saw him in court wearing a suit and tie, I thought he could have passed for a banker, college professor or even a prison warden.

Albert had long ago made a decision not to fret at being behind that high chain link fence. Rather than become bitter, complain or attempt to escape, he concentrated on building relationships. When I met him he was in charge of the hobby shop at Matsqui. Prison staff at times came for a chat, and within the confines of his assignment, life appeared surprisingly normal. Like the Bird Man of Alcatraz, he had found meaning within what was a harsh reality for most inmates.

At the B.C. Penitentiary I met Jim, a soft spoken burly man in his late twenties. His powerful physique might have given him entrance into the world of professional wrestling, if an inner void had not prompted him to seek solace in alcohol and drugs. He had murdered his girl friend while in a substance induced stupor. In the sombre grey world of concrete and steel bars, he could not find any meaning or purpose to sustain him. At night he was tortured by troubling images. He did reach out to our organization for a citizen sponsor, but the forces of darkness and despair overwhelmed him. When I phoned to arrange a second visit, the prison switchboard operator said, “I’m sorry, but Jim is no more.” He had hung himself in his cell.

At Menno Hospital in Abbotsford, I met Gladys, a former airline hostess. At about age 40, her face still retained vestiges of former beauty. Now confined to a wheelchair by MS, she wasn’t able to adjust to her dismal reality. Angry and bitter, Gladys refused all overtures of friendship. I attempted to engage her in conversation several times, but she just lashed out at the unfairness of life. When she was transferred to another institution, she left without saying good bye to anyone. Life had become something to be endured.

Eighty-three year old Anna was a resident in the same facility. As a young woman she had lived with her husband and two children on a collective farm in Ukraine. After Communist agents took her husband away, she never saw him again.

Anna was endowed with a streak of daring. During WW II she escaped to Germany, then emigrated to Canada. Here she created a good life for her family. Then, at age 82, shortly before I met her, she climbed a cherry tree to enjoy the fruit. A branch broke and she fell. Her aged body never recovered. Now in a wheelchair and totally dependent on others, she spent her days in the dining room, always wonderfully cheerful. One day as I was about to leave, she grasped my hand firmly and spoke a blessing over me in her native German. I wondered if she knew she wouldn’t see me again. A few days later this cheerful elderly saint went to meet the God she trusted.

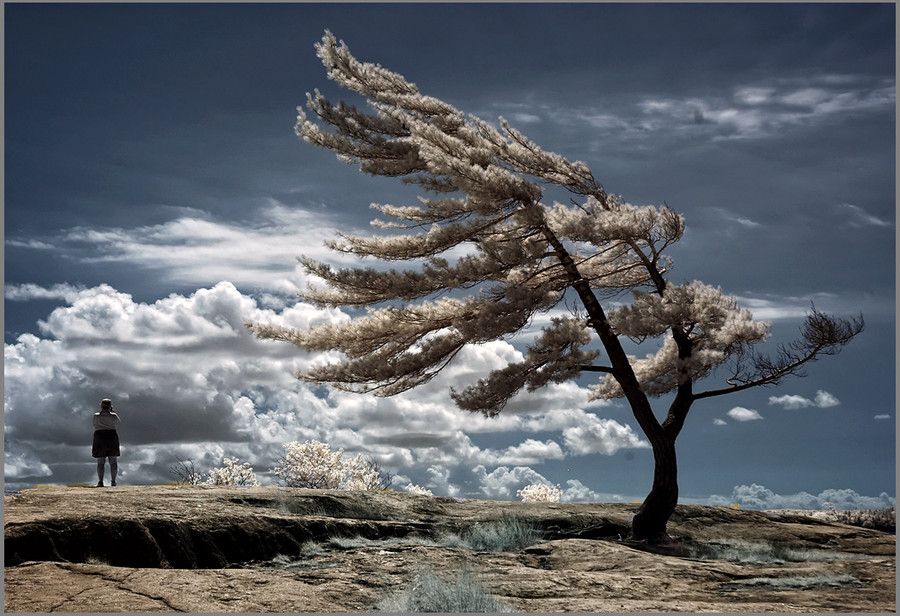

Headwinds along the path of life are inevitable. We can complain, cringe or buckle. Or we can choose to dig deep for the resolve to persevere.