The following talk was written and delivered by William Day at the Hedley Remembrance Day ceremony November 11, 2019.

War and Remembrance

Warm thanks to Jennifer Douglass and Andy English of Hedley, whose research into our Hedley Boys of World Wars 1 & 2 has provided a wealth of information for us. I also thank Wade Davis of UBC who has done deep research into the Great Wars of the 20th century. These people have made this presentation possible.

Winston Churchill called the period 1914 to 1945 the Thirty Years War. Clearly, the 20th century was the most destructive of lives in world history. Millions upon millions of lives were lost and ruined. Despite the references to World Wars One and Two, it was a single spasm of destruction whose impacts we continue to feel and with which we struggle today.

At the outbreak of the conflict in August of 1914 a man had to stand 5’8” to enter the British army. Within two months boys 5’3” were eagerly recruited. In eight weeks the British Expeditionary Force, four divisions – about 100,000 men – that represented the entire home army of the British Empire, had been virtually annihilated in the first industrialized slaughter in human history.

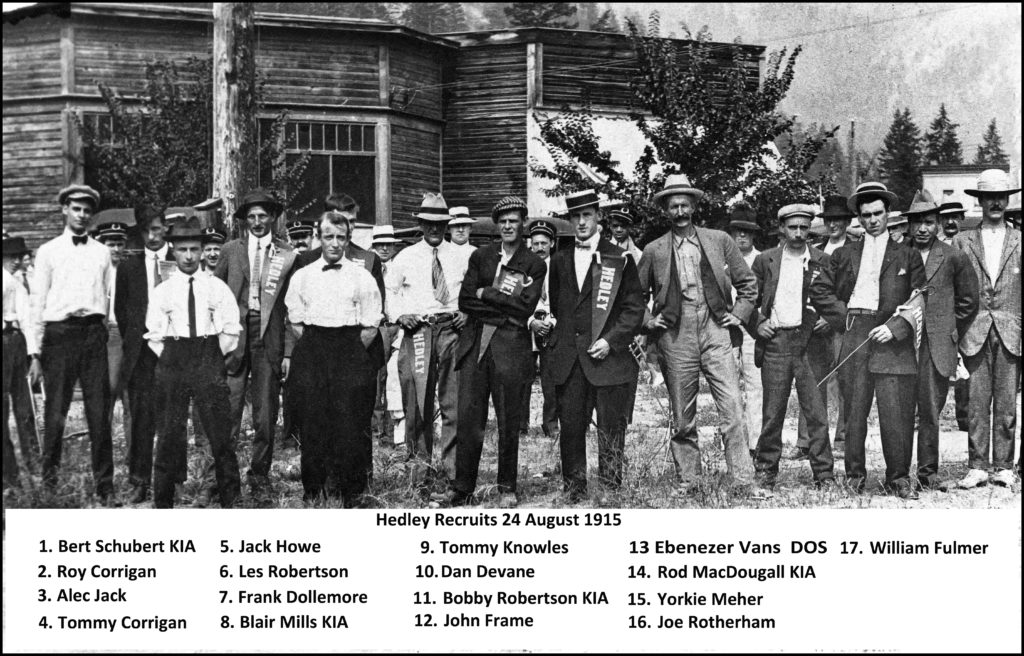

The Hedley Boys, seventeen of our own men – mostly very young – died while on service in WW 1&2. Killed in Action: 10; Died of Wounds: 5; Died on Service: 2. Hedley men were sought after – a population of young, fit men who were familiar with underground work, heavy machinery and explosives.

Most Canadian lives were lost in the Ypres Salient in Belgium during World War One. This was a section of the battlefield surrounded on three sides by German forces. It measured only four miles by twelve – roughly the land valley area between Hedley and Princeton. In that cauldron of warfare 1.7 million boys and men would die in 1915 /16 and 1918. The Canadians became famous for their holding of the Allied lines near Ypres under the first gas attacks even as allied forces on all sides panicked and fled the field. They became the shock troops of the British Empire for the remainder of the war.

The horrors of the warfare near Ypres are difficult to comprehend. The corpses of over 90,000 British and Canadian dead at Passchendaele were recovered too severely mutilated to be identified. An additional forty-two thousand disappeared without a trace.

By the spring of 1918 the greatest security challenge for the Allied command was concealing the location of the Canadian Corps, whose presence at any sector of the Front implied to the Germans an imminent major assault.

The truth lay in the numbers. World War One yielded nearly a million dead in Britain and the Dominions alone, some 2.5 million wounded, 40,000 amputees, 60,000 without sight, 2.4 million on disability a decade after the end, including 65,000 men who never recovered from the “twilight memory of hell” that was shell shock. And the Great War of 1914/18 was just the precursor to the Second World War of 1939/45. This conflict killed and wounded double those numbers plus an equivalent toll in civilian lives.

In May 1915 following the death of young officer and friend Alexis Helmer, Canadian army surgeon Dr. John McCrae wrote the fifteen lines of the poem – In Flanders Fields – that, more than any other, would distill the anguish of 1915, a time when there still remained hope that the conflict ultimately would have some redemptive meaning. He chose as a symbol of remembrance a delicate flower, quite unaware of the cruel irony that poppies only flourished in the fields of Flanders because constant shelling and rivers of blood had transformed the chemistry of the soil. “In Flanders Fields” survived the war and is the most remembered evocation of the conflict. Like so many others, McCrae did not. He died of pneumonia at Wimereux, France on 28 January 1918.

In Flanders Fields the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row

That mark our place, and in the sky

The larks still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard among the guns below.

We are the dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow

Loved and were loved and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Hedley was designated in 1919 as either the very first or one of the very first Canadian communities to formally create a memorial for people who served in the armed services of the Great War. The Cenotaph in front of which we are standing is that memorial, now including our people from World War Two and the Korean War. Many people here today can feel proud of their contribution to maintaining and preserving this beautiful memorial.

The Hedley Boys joined the armed forces like young men everywhere on both sides of the conflicts – a desire for change, adventure, excitement in lives that felt routine, boring, even stifling. The thought of becoming a victim of a mass slaughter in the millions was far from consciousness.

On this, the hundredth year since the end of the First World War, it is timely to think not just of the young men and women who “joined up”. We should remember those who remained, enduring loss and loneliness and increasing strain in maintaining their communities.

It is also time to consider and celebrate the ongoing contribution of all those who continue to contribute to their community here in Hedley. They are right here, right now, and should be recognized as the foundation of our community and our own world. Look around you. These volunteers maintain and develop our world every day. They deserve recognition and gratitude for their contribution.

Thank you, All.

William Day

November 11, 2019