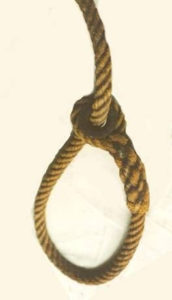

In 1967, the year I enrolled as a student at SFU, Canada’s Parliament had a change of heart concerning hanging. This didn’t impact my life, but I’m certain Rene Castellani was deeply relieved. He was in court at the time the bill was being stickhandled through Parliament, charged with the death of his wife Esther. She loved milkshakes and he had laced them with arsenic, bringing them to her even when she was hospitalized. Two weeks after the moratorium was announced, he was convicted of murder. Without the change, he almost certainly would have had a black hood placed over his head and a noose slipped around his neck.

(bcbooklook.com)

I came to know Rene quite well during his years at Matsqui Institution. Prior to his incarceration, he had been a highly regarded personality at Vancouver radio station CKNW and possessed exceptional PR skills. Unfortunately, his judgment became seriously impaired when he entered into a romantic relationship with a switchboard operator. He showed me photos of himself at a gala event attended by political and business elites He denied guilt to the end, but the evidence against him was deemed quite sufficient to convict him. Rene was paroled after 10 years, then died of cancer at age 57. Undoubtedly some innocent men were hanged prior to the moratorium.

Before the demolition of the B.C. Penitentiary, my duties at times called me into that foreboding institution of forlorn souls. On one occasion, a staff member escorted me through a spacious open area. Looking around, I saw only dull grey concrete. About a dozen disconsolate, grey clad men stood purposelessly around the perimeter. Their demeanor suggested they had no reason for hope or optimism. A skinny desiccated elderly man listlessly pushed a broad broom across the grey floor. The Penn has been torn down since then and some inmates were transferred to Matsqui Institution in rural Abbotsford. Here the atmosphere was less sombre and oppressive. Inmates could acquire work skills if they chose to. It was still prison, with two high wire fences topped by razor sharp wire. With no grey floors or walls though, it was a significant step up when compared with the dreary B.C. Penn.

At Matsqui, one inmate I came to respect was Albert, better known as Red. In his early 60’s, his copper coloured hair was tinged with grey. He had long supported his addiction to heroin with small scale trafficking. This “business” side of the heroin had landed him in several federal prisons. In spite of the many lost years, Red wasn’t devious or bitter and never attempted to use me to obtain favours. His responsibilities in the hobby shop gave him opportunity to talk without guards near by. He presented well and on escorted passes to purchase supplies for the hobby shop, he wore slacks and a sports jacket. At times his appearance and gracious manner led people to mistake him for a prison official.

Albert completed his sentence and returned to his usual haunts in Vancouver. At his age and lacking marketable skills, all he knew was trafficking. Heroin owned his soul. He sold a small quantity of the then highly illegal substance to an undercover officer and was sentenced to another 8 years. Laws concerning trafficking in even small amounts of heroin were much tougher then.

Over the years lawmakers have wrestled with our criminal justice system in an attempt to make it more humane and also more effective. Even so, as Canadian Senator Kim Pate has said, “Prisons are not treatment or mental health centers.” We’re allocating immense resources to redeem individuals who have been shaped by years of “jail house education.” Because of their criminal lifestyle and years of confinement, too often this is a futile effort.

Reflecting on Rene Castellani, the skinny inmate sweeping with a broad broom, and Albert at Matsqui Institution, I was prompted to ponder about the innocent, fresh faced youngsters in Similkameen schools today. Some will be lured into drug use and a life of crime. No government at any level has demonstrated the vision or will to forestall this likelihood. As a society, we need to allocate more funds to support parents, grandparents, schools and communities in their efforts to positively shape the thinking and actions of the next generation.

.

One thought on “Rene Castellani, Prison and Children”