CARD #: 2002725014

I remind myself occasionally of the 18th century story about an elderly man who often sat at the gate to Damascus. Over the many years of his life he had served the people and had attained considerable wisdom. Now, no longer having official responsibilities, he sat at the gate and greeted travelers as they entered the city.

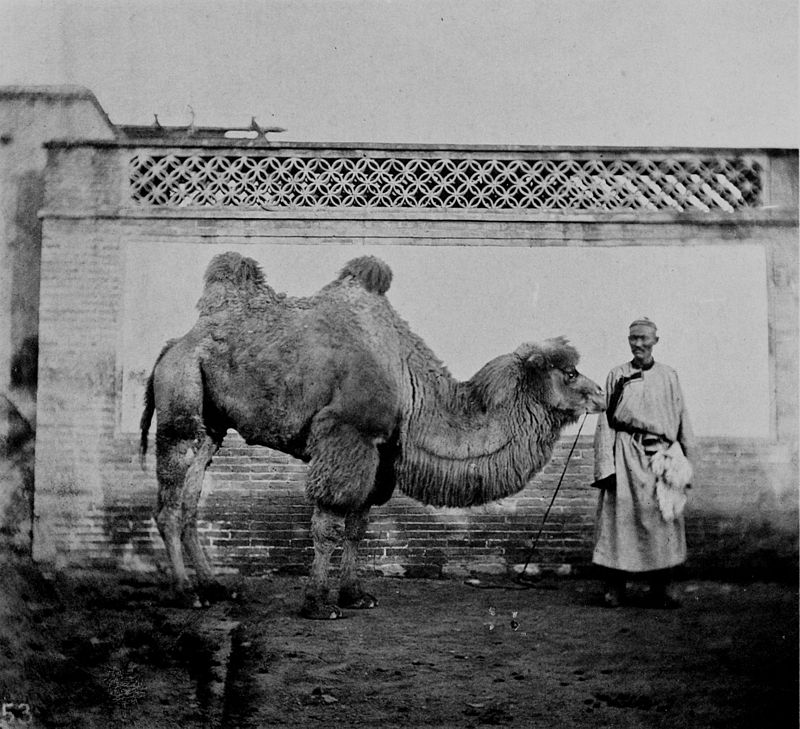

One day a merchant leading a camel train stopped and asked, “Can you tell me what sort of people live in this city?”

The old man considered for a moment, then said, “what sort of people live in the city you are from?”

The merchant’s face darkened. “They are a miserable lot,” he answered. “They cheat and rob and do harm whenever possible.”

The old man nodded and said, “Those are the kind of people you will find here.”

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

Another merchant, also leading a train of camels, asked the same question that morning. Once again the old man inquired, “what sort of people live in your city?” In reply the merchant said, “Oh, they are the most honest, trustworthy people I know.”

“You will find the people here are like that too,” the old man answered.

At the end of the day both merchants departed the city. Each stopped to tell the old man he had been accurate in his assessment of the people.

Contemplating this simple tale has helped me understand that my beliefs about people and circumstances can mislead me. Kurt Hanks, in Rapid Viz, suggests “We construct our beliefs, mostly unconsciously, and thereafter they hold us captive. They blind us to possibility.”

When Linda and I lived in a condo in Abbotsford, we had an opportunity to observe firsthand the lesson of the Damascus gate story. Living by herself on the same floor was Trisha, a blond with blue eyes and a figure that prompted men to pause for a lingering second look.

The first time she met Trisha in the hallway, Linda said “We’ll have to get together for coffee.” Trisha’s response was surprisingly unreceptive. “I have my own friends,” she said. When we met her after that, she greeted us but didn’t want to stop to chat.

For some time we were not aware of anyone other than Merla, seemingly her only friend, coming to Trisha’s door. We didn’t understand how such an attractive individual could choose to live with almost no one in her life. In time she acquired a live in boyfriend. He was evicted a number of times, according to the dictates of her moods.

When I was elected to the condo council, I learned that Trisha had recently complained about water damage to her living room ceiling. Although the problem had been dealt with and the ceiling repainted, she began telling residents she wasn’t receiving the same consideration as other owners. To satisfy her, council had actually already spent more strata funds in her unit than in others. She became increasingly uncommunicative in the hallways. When people met her, she looked intently at the floor and remained silent.

Trisha appeared to be developing an inner reality that did not exist outside her mind, seemingly blinded to the possibilities around her. A number of residents wanted to be her friend. They wanted to include her in the strata’s flourishing social life, but she invariably declined. To give her a voice in decision making, Trisha was elected to the strata council. The next morning she abruptly resigned.

She began focusing her growing anger on 78 year old Bert, the strata president. She apparently believed he was responsible for her inner misery. One morning we found a note had been slipped under our door during the night. It was from Trisha, addressed to Bert. It listed various, vague grievances against him. We learned copies of this note had been slipped under each door. In the coming weeks, there were a series of such notes. Their increasingly venomous tone disturbed some elderly residents. Bert continued to greet Trisha with a friendly face and uplifting words.

In retrospect, I’m sure Trisha sincerely believed it was unsafe to trust anyone. Three marriages had failed. She had terminated the relationship with the live in boyfriend. Her friendship with Merla was floundering.

By their beliefs and actions, Trisha and the first merchant entering the Damascus Gate created an unsatisfying, discordant personal world. Bert and the second merchant saw the good in people and thereby created a joyous, fulfilling personal world.

One thought on “Lesson Of The Damascus Gate”