I’m convinced local Similkameen artist Harvey Donahue views the world through a very different lens than most of us. Where we might see only an abandoned house bleached by the sun, or an ancient, decrepit logging truck left to rust in the woods, Harvey is likely to see unique beauty. For him these relics of the past could be worthy of an honoured place on his canvas. “Old houses can be beautiful,” he told Linda and me. “When I see one, I’m inspired to paint.”

I first heard from Harvey almost 2 years ago after I wrote about Bill Robinson’s iconic cabin along the Sumallo River in Manning Park. “I painted that cabin and the outbuilding before they fell into disrepair,” he said. “I’d like to send you a copy of the original.” That was the beginning of a phone relationship until he visited our home two weeks ago. On that occasion he surprised us with the framed, original painting of the snow bedecked Robinson cabin and outbuilding. For some reason known only to himself, he very generously presented it to Linda and myself. It is likely the best representation of that scene in existence today. It’s a gift we prize highly.

Being raised in Lac Ste. Anne, a Metis village in Alberta, very likely played a key role in the formation of how Harvey views the scenes and people around him. Now age 80, he retains vivid memories and images of those early years. He recounted them as though talking about individual mental snapshots from his past. “I started trapping when I was about 7 or 8. When my uncle moved away, I took over his trapline. Mostly I trapped weasels and sent the skins to a company in Edmonton. There was an annual pilgrimage of Metis people to our village. Some Cree came too. I attended school only until I completed grade 10,” he said. “Metis youths were encouraged to drop out after grade 8. We were called half breeds. I grew up feeling shame at being Metis. I used to tell people I was French. I remember that my dad had a few cows, some chickens and a garden.”

Although there wasn’t money for art lessons, he began painting at age 10. “When I was 14,” he remembers, “I painted a mermaid luring a ship onto the rocks. I still have that painting.”

His negative view of the Metis heritage began to shift at about age 20. “I decided I should be responsible for my existence. I began studying my Metis heritage and learned that my grandfather Gabriel Balcourt supported Louis Riel. He is listed on a plaque naming supporters.”

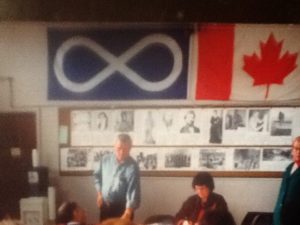

Harvey’s first wife was Metis and they had 4 children before she passed away. As he matured, his appreciation of the Metis heritage blossomed. “I became proud of being Metis,” he said. After moving to the Lower Mainland, he started a Metis organization and built it to 500 members. He is gratified that it is still functioning.

Harvey believes the Metis heritage shaped him. His life experiences, including the early discrimination, seem to have given him an understanding that we should not be quick to discount or discard our past. I sensed he has come to a deep realization that a historic structure or event represents what was important to people at an early time and place. It tells us about their culture, values and life experiences. It’s a connection with our past.

“When I see a scene that is likely to disappear, I take a picture and paint it,” he said. “I paint heritage scenes so they won’t be lost to the next generation.”

As an example he told us about one painting that depicts an old truck standing near a grove of trees. “Shortly after I completed that painting,” he told us, “the trees were cut down.” Sometimes he adds something to a painting. One of my favourite scenes is of the one way bridge in Princeton. He placed his own pickup truck in this picture.

Harvey views the Similkameen Valley with the watchful, observant eyes of an artist. “When the sun rises in the east,” he said, “you see subtle colours in the west.” He paused and then added, “art and music are important. They help us appreciate life, the past and the present, that exists all around us.”

One thought on “Through An Artist’s Lens”