My Dad grew up on a remote, infertile Manitoba farm. During the Great Depression of the 1930’s, his father had difficulty feeding and clothing a wife and 9 children. Their soul wrenching poverty didn’t encourage expressing thoughts such as “I love you.” When Dad fell at age 89 and broke a hip, he required the assistance available only in a longterm care facility. It was the beginning of a relationship adventure for him and me.

In my early years, Dad worked as a logger in the steep mountainous terrain back of Hope. Strong, skilled and rugged, he was away 2 weeks at a time and I didn’t get to know him well. Eventually he brought his big bulldozer back to the Fraser Valley. Then, in summer he took me along to his jobs and taught me to operate the dozer, front end loader and backhoe, use a chain saw and blow huge stumps out of the ground with dynamite. Although this wasn’t what I wanted for a career, it provided an opportunity to know and respect Dad.

He enjoyed music and played the violin. I was about 8 when he bought a 12 bass accordion for me, then later upgraded it to a 120 bass. He hoped I would make music with him. I didn’t share his enthusiasm for music though and when I moved out of the family home, I left the accordion and the music behind.

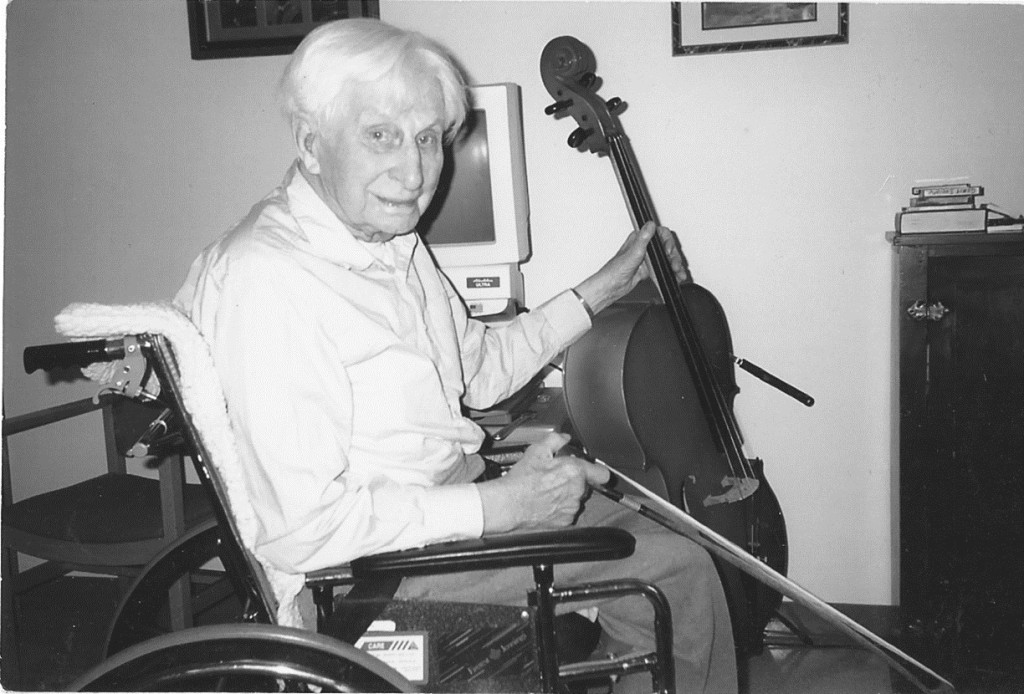

In mid-life, Dad bought a bass fiddle and joined a seniors’ orchestra. Years later, just prior to his life altering fall, he bought a cello and taught himself to play it.

When he fell, his head struck the floor hard and erased his memory of music. For two years my white haired Dad spent many hours, hunched over in his wheelchair, awkwardly grasping the instrument in a futile attempt to revive his skill. When I engaged a cello instructor to teach him, Dad devoted hours to practising. In his many sleepless nights, he mentally rehearsed musical scales.

Making music with his children was what Dad had dreamed of from the beginning. Now he needed someone to play with so I sat down at the piano in the common area and began to apply what I’d learned on the accordion. It wasn’t pretty, but I learned a few tunes. Each time I came in he’d say, “let’s go to the piano.”

We learned old time songs like “You’re Cheatin’ Heart,” “You are my Sunshine,” and “The Tennessee Waltz.” He had a deep faith in God, as did some of the residents, so we included such numbers as “The Old Rugged Cross” and “Amazing Grace.” Some residents drew close to us in their wheelchairs. Others quietly sang or tapped fingers on a table. At the end they applauded with their frail aged hands.

In time, holding the cello became difficult and Dad wearied more rapidly. His strong, rugged face could no longer hide the pain. Even when he grew too weak to hold the cello, he continued to say, “let’s go to the piano.”

Several nurses counselled me to tell Dad it’s ok to die. I did tell him if he chose to let go, the family would be ok. He fixed his clear blue eyes on me and said, “I still like to live.”

This reminded me of a time when I watched him on the big bulldozer, cutting in a road along the side of a steep ravine. A mistake would have sent him and his machine hurtling down. Now, white haired and no longer able to even get in or out of bed without assistance, this was just another difficult challenge. As long as he had music and his faith in God, his life had meaning.

When he was no longer strong enough to sit in his chair, I stood beside his bed, holding his hand. Sometimes, when the pain in his beleaguered body caused him to twitch and groan, I turned away, knowing my tears would trouble him.

One day, overcome by his helplessness and discomfort, I took his big hand and said, “I love you Dad.” He fixed those blue eyes on me and quietly said, “I love you too.”

One night, in his 95th year, the phone rang at 5:05 a.m. A nurse said, “your father has just passed away.” I was deeply saddened, but comforted by the thought that we had learned to say “I love you.”

I enjoyed the story about dad. You were a wonderful support giving him a reason to want to continue to live.

That is a beautiful tribute to a well loved Dad.