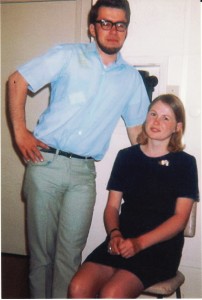

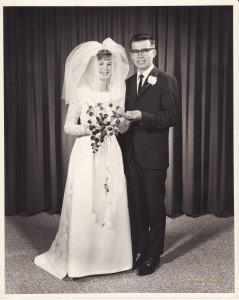

At the beginning of our SFU journey, Linda and I rented a poorly heated basement suite from an elderly widow in Burnaby. For some reason, she didn’t trust us. Possibly she was aware that at times I kept a light on while I worked through the night preparing assignments due the next day. This expense may have agitated her. Possibly she thought that since I was a student at SFU, we must be communists.

Our landlady evidently felt a need to keep us under constant surveillance. When we went away, I sometimes placed an object behind the door to our suite. Often it had been pushed back, so we knew she had entered. When my parents came to visit, she just happened to be doing a little gardening at our living room window. At one point she sent us to her son to be interrogated by him. He was a decent man and appeared to be as mystified by his mother’s suspicions as we were.

After three months of this, we told her we would be moving out. She said “that’s good, then I won’t have to evict you.” We had paid our rent faithfully and had caused her no problems. Her seeming unfairness brought out the worst in me and I was tempted to tell her we were Communists, but she was an elderly woman and I thought better of it.

After that we moved into a two room suite in the front end of the old B.C. Tel office on Gladys Avenue in Abbotsford, across the street from several sets of railway tracks. Initially the train whistles and rumbling of the wheels on the tracks woke us at night, but after a few weeks we were able to sleep through this. Linda got a part time job at the Royal Bank and I carpooled to SFU.

I had begun with a history major. When I discovered the PSA department (political science, sociology and anthropology), I switched. Sociology became my main focus. It was in PSA that my real education began. A number of extremely radical American professors had made their home here. One was an avowed Marxist. The others weren’t far behind. They focused on the evils of the capitalist system. I was assigned to read “The Communist Manifesto,” “Red Star over China”, “The Wretched of the Earth”, and “Soul on Ice” (by Eldridge Cleaver, a leader in the Black Panthers), etc. They held up Fidel Castro and Che Guevara as icons.

The PSA professors seemed motivated by a zeal to radicalize us. They wanted us to rebel against the traditions and values of our society. Several of them seemingly believed that to accomplish this they must first wreak havoc in our minds. They were smart, well informed and able to communicate their ideas in a way that caught our imagination. In time they succeeded in fostering a radicalization among many students, especially in the PSA department, but also in other departments. Eventually charismatic, radical student leaders persuaded a significant number of students to participate in a strike and occupy the administration building. This resulted in an early morning raid by the RCMP.

In the midst of the growing agitation, there were other groups, such as the small contingent of hard-core Marxist Leninists who had their own agenda for world revolution. I was particularly fascinated by the Hare Khrishnas in their hooded light brown robes shuffling in tight circles chanting words unintelligible to me. The Hippie movement was also gaining momentum and I was amazed at first that guys would let their hair grow to shoulder length and walk around barefoot in torn jeans. Marijuana, a drug about which I knew nothing and with which I had no experience, was in vogue.

To enhance our understanding of the damage done to Aboriginal culture by white society, 3 PSA profs organized a Royal Hudson train trip to the Mount Currie Indian Reserve near Pemberton. I was sitting in a circle with other students and a skinny “ rollie” was passed around. Each time it came to me, I accepted it and took a drag. Only later did it occur to me that I had been smoking pot. This was early in my days at SFU and I was still the small town boy who had lived a pretty sheltered life.

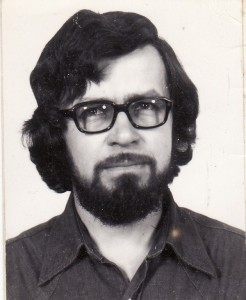

I attended many of the noon hour meetings organized by the leftwing student leaders. Sometimes the speaker was Martin Lowney, who was generally thought of as the key spokesperson and leader. Martin proved to be a charismatic personality with an ability to whip up emotions. By exposing myself to their ideas, I was being inexorably and increasingly drawn in by the philosophy he and others espoused. I’m sure my parents and also our friends in Abbotsford were astonished at the change in my appearance. I

grew long sideburns and then decided to allow them to meet , which meant I had a beard. Also, I stopped going to the barber and my hair grew very long. My brother in law gave me a pipe which, like other students, I sometimes smoked in the tutorial classes.