I was astonished and perplexed recently when I learned that two ladies I know have not spoken to each other for 20 years. Both are respected and well liked, contributing members of their community. Although by no means as serious, their fractured relationship reminded me of the infamous Hatfield-McCoy feud in the U.S. Appalachian region.

The latter dispute is believed to have been instigated by a pretty minor matter, the alleged theft of a pig owned by a McCoy. Curious as to the dynamics underlying longstanding disputes between people, I felt prompted to delve into the circumstances of the Hatfield-McCoy clash.

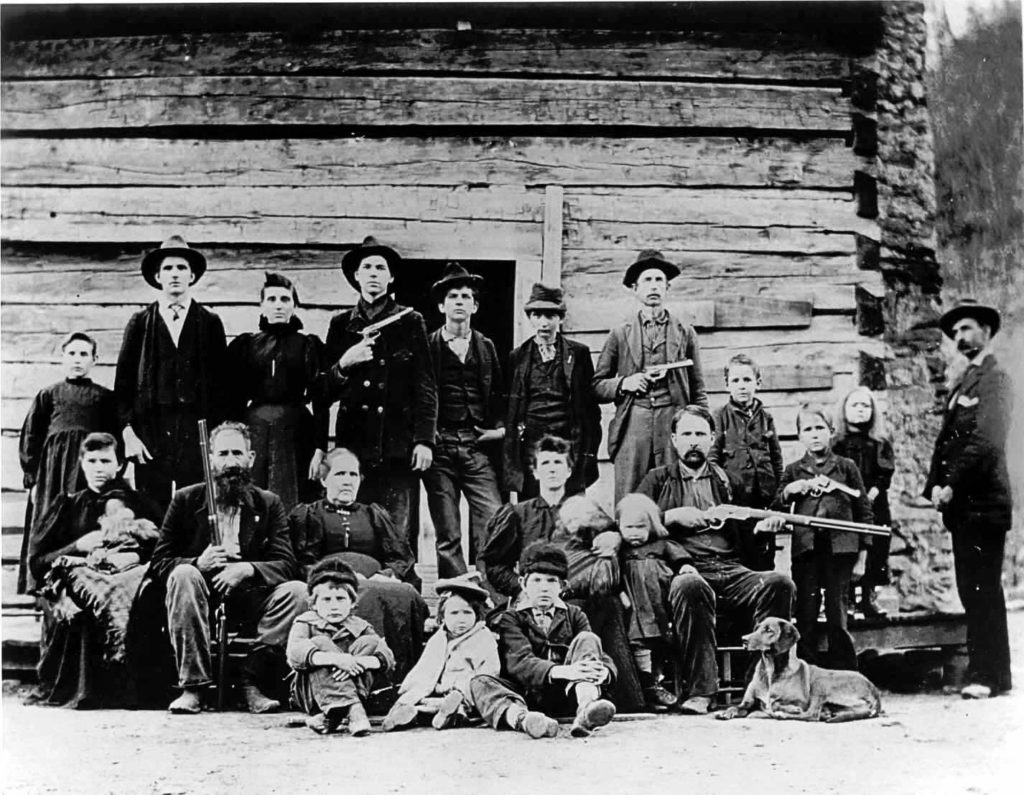

I learned that the 2 clans lived on opposite sides of the Tug Fork, a stream running along the border between West Virginia, where the Hatfields lived, and Kentucky, home of the McCoys.

Although other factors, like land disputes and differences of opinion concerning the Civil War may have played a role in the feud, the initial catalyst is believed to have been the pig matter. In 1878 a McCoy claimed to have seen the missing hog on a Hatfield property. The case went to court in West Virginia and the Hatfield won. Known for volatile tempers, the McCoys over reacted. Their anger smouldered for several years. They didn’t forget.

In 1882 a brawl erupted between members of the families and Ellison Hatfield was mortally shot by a McCoy. From there the feud escalated. Seeking revenge, the Hatfields kidnapped and executed 3 McCoy brothers. After that the two families repeatedly ambushed and killed one another. In 1888 a group of Hatfields attacked the home of Patriarch Rand’l McCoy, shooting his son and daughter and burning the family homes.

The McCoys, led by a Kentucky deputy sheriff, made several raids into West Virginia and and killed 4 Hatfields. They arrested 9 more and the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In what seems like skewed justice, nine Hatfields were sent to prison, seven with life sentences. One was subsequently hanged.

The feuding continued into the 1890’s, but in time the families apparently decided the price of revenge was exacting a toll they were no longer able to bear. Possibly wiser leaders prevailed. In 1944, Life Magazine showed the families getting along amicably.

It’s difficult to imagine a feud of this magnitude here in the Similkameen Valley, or anywhere in Canada. Occasionally though, we do hear of individuals taking a perceived slight or disagreement so seriously they never speak to each other again. This is particularly tragic when the falling out is between family members.

When I was chairman of a strata council, one member regularly picked fights with our property manager. Gregory repeatedly demanded expenditures that would decimate our contingency reserve fund. I agreed with the property manager and Gregory added me to his most despised list. An avid fan of the internet, he plied council members with messages about my various failings. In time, the unrelenting torrent of abusive e-mails began niggling deep within me and I realized they were influencing my thinking about him.

Fearing the erosion of my sense of fair play, I called him in the hope we could have a constructive discussion and learn to work together. Almost immediately, I realized Gregory had deemed me irrevocably guilty and was unwilling to move beyond this decision. At the end of that year I resigned, wanting someone untainted in Gregory’s mind to take the helm.

Unfortunately Gregory passed away 6 months later and I did not have another opportunity to mend that fence. He wasn’t a bad person and in retrospect I realize the outcome could almost certainly have been more positive. I really should have reached out to him before the negative thoughts had become set in mental concrete.

Experience over many years has convinced me that when we harbour resentment and shut people out, we become depleted at a deep level. Refusing to seek reconciliation suggests encrusted thinking.

Even the Hatfields and McCoys eventually learned to be friends. They now enjoy a joint family picnic on the second weekend of each June. There are skits, home cooked meals, musical events and a good natured tug of war across the Tug Fork.

For reconciliation to begin, one individual needs to reach out. Such attempts will not always be successful, but my experience with Gregory suggests it’s best to seek healing before the anger festers. Theft of a hog need not cause a feud.

One thought on “Lessons Of The Hatfield McCoy Feud”