In this 150th year of Canadian nationhood, our politicians could benefit from an examination of the life of Poundmaker, the Saskatchewan Cree chief. He lived during a time when his people were in great distress and turmoil. White settlers were invading the prairies and pushing his people off their land. The immense buffalo herds on which they depended for their livelihood were being hunted relentlessly. Government treaties were forcing them onto reserves and restricting their movements.

Born in 1842, Poundmaker was the son of a Stoney father and a mixed blood mother. His uncle was an influential chief of the Eagle Hills Cree. Later he was adopted by Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet, and lived there for a time before returning to his people.

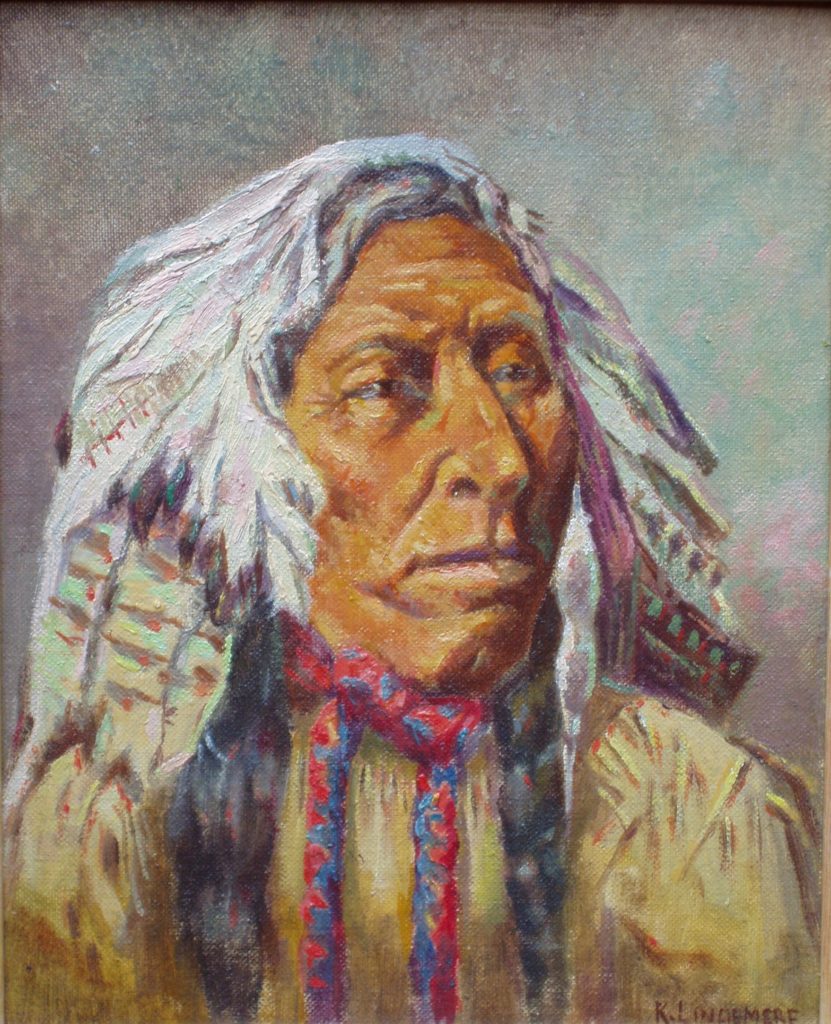

He was endowed with leadership ability and probably learned a lot from Crowfoot. Robert Jefferson, farm instructor on the Poundmaker Reserve said later, “his bearing was eminently dignified and his speech so well adapted to the occasion as to impress every hearer with his earnestness and his views.”

In 1876 the Indians of Central Saskatchewan negotiated a treaty with the government of Canada. As a member of the negotiating team, Poundmaker sought to obtain the most beneficial deal for his people. His discerning mind questioned the intent of the government and he expressed his concern. He wanted the government to provide his people with instruction in farming and assistance after the buffalo were gone, in exchange for their land. The government did not promise this and he said, “I cannot understand how I shall be able to clothe my children and feed them as long as the sun shines and the water runs.”

He was made a chief and in 1879 he accepted a reserve. He moved there with 182 followers.

For a time the government did provide food, but in 1883 the rations were reduced. It was rumoured that the rations would soon be eliminated entirely and the people left to starve.

The winter of 1883-84 was extremely severe and Indian agents complained that many people would not live until spring if the government didn’t provide more provisions. The government ignored these pleas and Poundmaker’s young men became restless. Young Crees and Stoneys, as well as Metis, began assembling on the Poundmaker reserve. They set up a warriors lodge in the centre of the camp and thereby, in accordance with tradition, took over decision making. Approximately 1000 people gathered and participated in a Thirst Dance.

The government sent a column of 325 men to arrest a band member. Poundmaker declined to give the man up, and offered himself instead. This was refused and government forces attacked Poundmaker’s camp at Cut Knife Hill. After a 7 hour battle they retreated in disarray. The warriors wanted to pursue them and could have dealt them a serious blow. Poundmaker was still greatly respected by the young men and when he counseled against further bloodshed, they listened.

At the same time, the Metis were in armed opposition to the government. When a group of them captured a government supply train Poundmaker intervened, ensuring they were protected and well treated.

After Louis Riel was defeated at Batoche in 1885, many of Poundmaker’s men wanted to continue the fight but he understood the futility of this. At a gathering of the band, he said, “ I know we are all brave. If we keep on fighting the whites, we can embarrass them, but we will be overcome by their numbers, and nothing tells us that our children will survive. I would sooner give myself up and run the risk of being hanged, than see my tribe and children shot through my fault.”

He and some followers gave themselves up and were immediately arrested. Poundmaker was put on trial for treason. The men he had saved from the Metis testified he had treated them generously and with compassion. Even so, he was sentenced to 3 years in Stony Mountain prison. Due to fear of a full blown revolt if he died in prison, he was released early. In ill health, he departed broken and dispirited, feeling betrayed by the government. While visiting Chief Crowfoot, he died while participating in a dance.

Poundmaker was a man of great honour and dignity. He was guided by a selfless desire to secure a good life for his people. Our nation would benefit if more politicians observed his honourable example.

One thought on “Poundmaker, A Role Model For Today’s Politicians”